To know every day that you are putting your ideas, your worldview, your commitments and your self on the line every time you step up and face something new is an act of pure courage. Where does that fit on the bell curve?

This week in my IASK (Integrated Analytical Skills and Knowledge) courses, we began exploring in earnest how to formulate a good question. The students are moving into their research projects and are in the process of narrowing down their topics, so it seemed timely to get into the nuts-and-bolts of question-making.

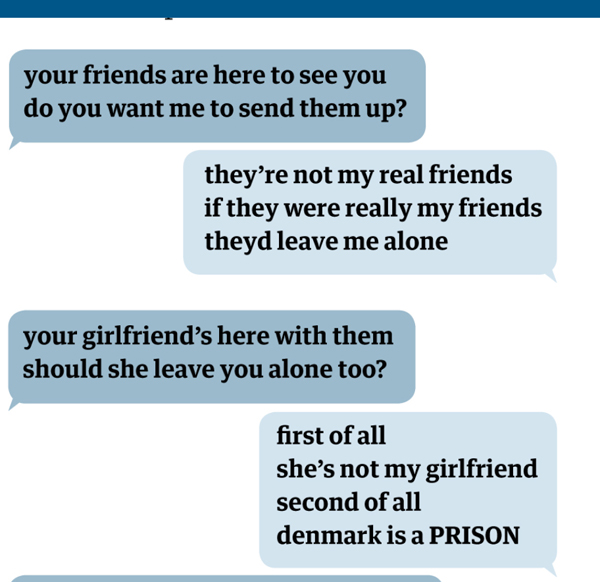

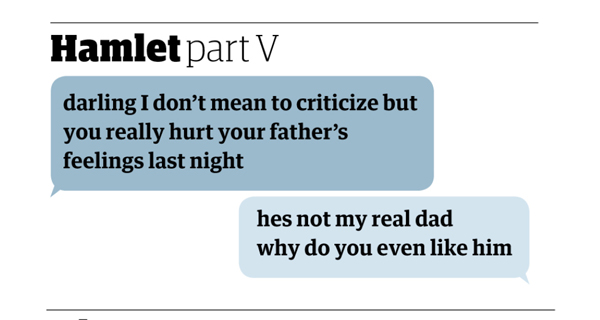

So, this post has a practical aspect and another, more… er… existential aspect. There are no actual unicorns. Sorry. Okay, maybe….

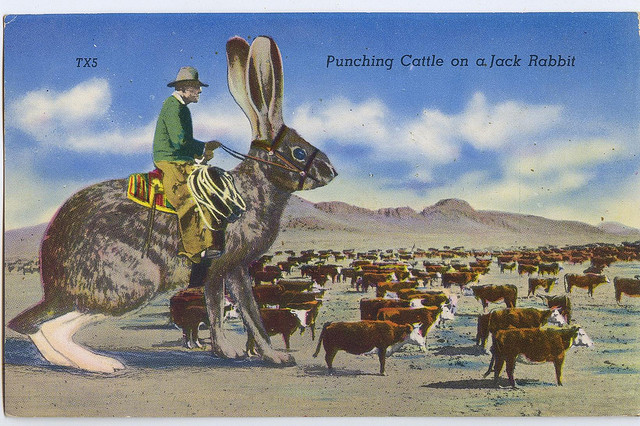

Northrop Frye once said (somewhere–I read all of his books for a course in graduate school, and, although they are, as you might expect, well-structured and well-labeled, they have run together in my mind) that an abstract picture should have a cow in it, because the cow lets people relax into the familiar so that their brains can accommodate the non-representational. The fact that the above image counts as the cow and/or unicorn in this post… well, I’ll let you draw what conclusions you will about me, this post, and, indeed, humanity.

The Practical Bit

If you’re looking for a good, handy, user-friendly aid to writing questions for your students, I would suggest this one:

Quick Flip Questions for the Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy by Edupress.

It’s compact, spiral-bound and comes with a hole punched in it so it can live in a binder. Plus, it’s inexpensive. It was especially inexpensive for our students because our awesome University Librarian, Alan Wilson, bought a whole whack of them as swag for students and each of our IASK students got one for free. Head on down to the Weller Library to see if they’ve any left. Woohoo!

For each level of Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy for Critical Thinking the booklet provides a description of the mental process involved, keywords associated with that level and sample question-starters. For example, the “Remembering” level prompts us to ask, “Can you select…?” while the “Creating” level prompts us to ask, “Can you construct a model that would change…?”

This week, we broke into groups and used the flip-book to construct a preliminary set of questions for the two readings we had on deck. I framed this exercise with a refresher on WHAT and SO WHAT questions, another way of articulating the relationship between the “Remembering/Understanding” levels and the “Applying/Analysing/Evaluating/Creating” levels. WHAT and SO WHAT are the “cattle” and “hat” of a good discussion or research project. That is: the generalizations of the SO WHAT questions or statements ain’t cowboys unless they’ve got a herd of WHAT to justify all that standing around in a field wearing a 10 gallon Stetson (Credit for this analogy goes to my Doctoral Supervisor, Tony Brennan, who described my dissertation as “All hat and no cattle.” He was right, and it was much better after his intervention. He also used to quote tragedies of blood to describe my work, which was a bit disheartening, although, admittedly, also correct and salutary in the case of my dissertation. That said, Macbeth is never really a good co-pilot, unless you are interested in how not to get away with murder. But I digress).

Sometimes, cowboys take interesting shapes. Not every essay looks like an essay. But there’s a hat and there’s cattle, a WHAT and a SO WHAT, so we’re good to go.

Here’s the PowerPoint presentation that went with that discussion: Asking Questions with some Help from Starfleet. And here’s the relevant tip sheet: Asking Questions Tip Sheet.

The key to the whole shebang is in the feedback. I should have incorporated this aspect more formally. The flip-book method gives an instructor a great opportunity to explore with students how to construct WHAT questions that lay the groundwork for the more analytical, critical SO WHAT questions and vice versa (depending whether you’re dealing with a naturally inductive or deductive thinker). With the flip-book to hand, you can help the students to choose sample “starters” that encourage them to clarify what they are really asking (see “Hidden Questions” in the tip sheet linked above) by honing in on verbs that capture particular aspects or actions of “understanding” (That most troublesome of waffle-words, a word so “baggy” that, like an over-sized shoulderbag, it accommodates so much as to be functionally useless as a conceptual tool). Working through the flip-book–whether linearly or in a more organic way–also provides a structure that allows students to see the linkages between the WHAT levels and the SO WHAT levels, increasing the possibility that they will begin to construct a coherent analytical “thread.” I’m a fan.

It remains to be seen if the students love it as much as I do. I encouraged peer2peer workshopping of the questions the students generated but did so in the context of a larger, time-crunched exercise, which was, in retrospect, an error. I think the better process would be to focus only on the question-crafting and peer2peer discussion and then fold that skill into the presentation-skills exercise in a subsequent iteration. I’ll see what the students think about that. They are a very thoughtful and game bunch.

The Existential Bit

I should have put the unicorn/cow here, I suppose. Here’s a quotation that I have on my door:

“In my view, the very highest passion is driven by non-knowing. It’s tensions are heightened and the stakes are raised when we lack assurance about what is going on, or how things will turn out, when all we can do is push on, have faith, keep going, love and trust the process about which we lack any final assurance” (John D. Caputo, On Religion).

I love this quotation because it validates the question–not the answer–as a way of life, as an orientation toward the world and toward knowledge. It’s not about measuring success according to the answers we’ve accumulated but rather our willingness to forge ahead with our questions, moving into that dark space of un-knowing. The moving pen pushes a bow-wave of anticipation onto the page, or, as Paulo Freire would have it: We make the path by walking.

This, it seems to me, is the essence of education. Not answers, but questions. Not questions but questioning. Knowledge, Caputo suggests, is not something you have; it’s something you do. In spite of its grammatical designation, knowledge is a verb. To question is to be in motion. Is that not, really, the definition of “life-long learning?”

We are doing a lot of work as educators to produce critical, dynamic, and adaptable thinkers. That’s what the flip-book is for, after all. It’s a protrusion into the practical of a much larger philosophical stance toward knowledge. Of course, we do a lot of this work at the same time as cutting the legs out from under it by insisting that showing up to a rodeo on a jack-rabbit is unacceptable. We do a great job of beating the joy of learning out of students, sometimes, largely by telling them, on the one hand, that we want them to be creative thinkers and then, on the other hand, informing them via our assessment models that to think outside the box is to risk getting a bad grade (Aha, you see why my unicorn is not a unicorn but a heart-chomping monster). There is a lot of really interesting work being done in the area of Personal Epistemology that demonstrates how students’ concern for grades actually impedes the kinds of learning to which we aspire (see for example, Pizzolato 2008; Marra and Palmer 2004, to name just two). We want to cultivate a love of questions, but very often we what we produce is a cult of answers. We make students afraid of their own open-endedness by building assessment models that emphasize closure; the “final” exam–it tolls for thee (apologies to John Donne).

When I was putting together my Powerpoint on Asking Questions, I threw in some examples from Star Trek. In formulating my SO WHAT question, I realized that this question about questions and how they are linked to our orientation toward our universe had been percolating for a long while. The sample question I provided to go with “How many of these red shirts are going to make it back from the away mission?” was: “What is the relationship between the idea of endless expendability and human confrontation of the unknown?” I surprised myself (brains are often way smarter than we are, y’know?). Is it true that we have in our minds a notion that to proceed into “the final frontier” (in the Trekkian, not Hamletian way) is to risk annihilation, and that the price of exploration is expendability ? Do our students see themselves as red shirts shoved onto the transporter pad and told to “think creatively,” to “boldly go where no-one has gone before,” all the while suspecting that the game is fixed (Surely those red shirts have noticed the pattern. Guy in Galaxy Quest sees it: ” I’m not even supposed to be here. I’m just ‘Crewman Number Six.’ I’m expendable. I’m the guy in the episode who dies to prove how serious the situation is. I’ve gotta get outta here.”)? The research seems to suggest so.

How do we create a culture of assessment and feedback that makes the question the paradigm? How can we communicate and model the idea for our students that knowledge is a verb and that failure to know is a condition of learning, not a sign that learning has failed? How can we show students an alternative stance toward the unknown that challenges the red shirt syndrome? If I might tip my hat to Jacques Derrida, I might ask: how can we promote the jouissance of learning, the joy of open-endedness, dare I say, the act of faith that leaping into the unknown demands of us?

Students are brave. To know every day that you are putting your ideas, your worldview, your commitments and your self on the line every time you step up and face something new is an act of pure courage. How do we truly acknowledge the value of that act of learning? Where does that fit on the bell curve?